STEM to Rural High Schools

SSU and Keysight Team Up

Students at six Mendocino County high schools are learning how to make homemade Geiger counters and mud-powered batteries thanks to a group from Sonoma State University and a $3 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education.

The project, Learning By Making: STEM Success for Mendocino County, will help prepare 460 students for college with cutting-edge science, technology, engineering and math experiments. "This is when the rubber really hits the road, because now we're rolling it out to schools," says SSU physics and astronomy department chair Lynn Cominsky, who designed the experiments.

The project began last year and fits the A to G curriculum, a requirement for entry into the California State University and University of California. "We were happy to get a D," project director Susan Wandling, referring to the curriculum's "laboratory science" requirement.

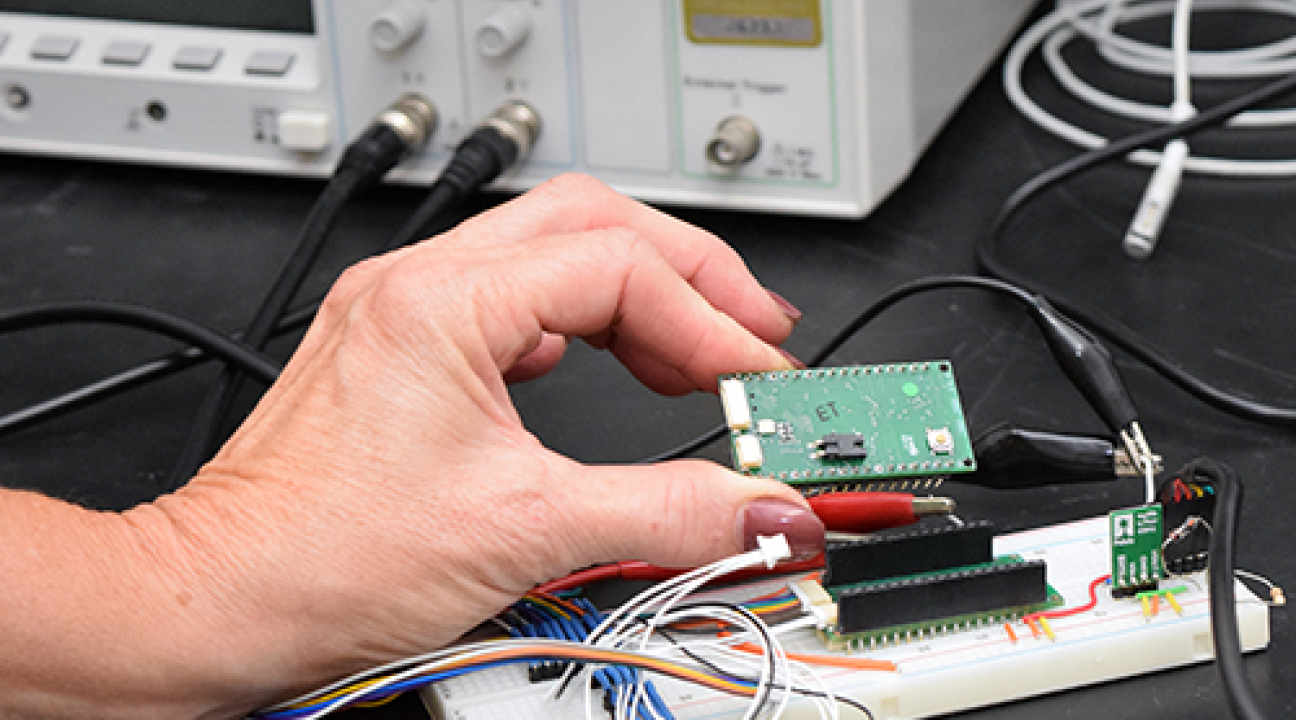

The technological heart of the experiments is a custom-designed, palm-sized electronics board, which is effectively a tiny computer. Each of the 90 boards has a microchip processor at its core, with 64 tiny pins that needed to be soldered on. Enter Santa Rosa's Keysight Technologies, which helped make one-third of the labor-intensive boards. "The work that Keysight has contributed is really helping us provide the school with the parts that are the hardest for us to make on our own," says Cominsky. "We couldn't have done this without their timely assistance."

Keysight is no stranger to the university. The company has a longstanding partnership with Sonoma State's engineering science department, and Keysight vice president Mark Pierpoint is co-chair of the department's Industry Advisory Board. So, when Cominsky asked Keysight engineer Helen Chen if she could help out with the Learning By Making project, Chen assembled a group of engineers who were glad to assist.

lbeit in small amounts,

thanks to naturally-occuring bacteria.

"Keysight is commited to supporting STEM education at all levels," says company spokesman Jeff Weber.

In the first year of the two-year project, students will learn how to build their tiny computers and program them before undertaking the first experiment, which involves measuring temperature to learn about heat diffusion through the earth.

Then it's on to building batteries out of mud. The "microbial fuel cell" experiment uses cathodes to convert energy made by aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in mud into electricity. "They only put out a little bit of energy, but if you hook them up together you can power something," says Cominsky.

A second experiment measures air quality, and the third experiment is a homemade Geiger counter, which will be used to measure radiation. The team at SSU is currently designing experiments for next year's curriculum.

The grant comes from the Department of Education's Investing in Innovation (I3) program. Sonoma State is one of 18 groups awarded a grant out of more than 600 applicants.