SSU History Department Sheds Light on Slavery in Sonoma County

Fortified with the promise of railroad travel, agricultural expansion, and booming ranch and mining operations, Sonoma County in the 1850s provided favor and opportunity for those who called it home.

Like many other parts of the country, with the growth of business came the need for labor, and despite the fact that California was considered a free state, the Fugitive Slave Act was passed 1852, allowing slavery to ensue in the republic.

With a commitment to uncovering local history and digging into Northern California’s surreptitious past, a Sonoma State summer research project has revealed that slavery was customary in Sonoma County.

"A claim we can make is that up to 29% of households in Sonoma County in the 1850s relied on coerced labor," said Sonoma State history professor Amy Kittelstrom, Ph.D. "We're seeing it was commonplace here, even after California entered the Union as a free state."

Now in its second year, the project is part of the university's Social Science Undergraduate Research Initiative (SSURI) and Community Impact Research Award (CIRA) program.

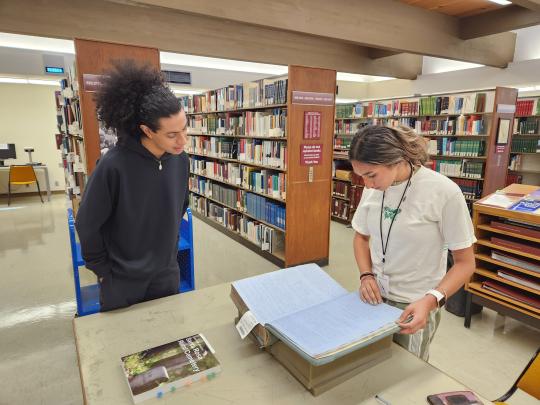

With help from the Sonoma County History and Genealogy Library, Kittelstrom began researching the project – “Slavery in Sonoma County from 1850-1865” – in the summer of 2023, along with SSU student researchers Jeremy Medrano and Juliana Chand.

Kittelstrom continued through the 2023-24 academic year with students Alycia Asai, Jason Herrera, and Cole Rubert, and will proceed with research fellows Yumiko Bellon and Luis "Mikey" Carrillo through the summer of 2025.

"I don't think I considered the reach of slavery this far west by the onset of the Civil War," Herrera said. "The research we've gathered shows that numerous communities within Sonoma County were exploiting the county's Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and Asian residents."

Kittelstrom said much of the evidence revealed by her team's research shows that Native Americans were disproportionately used as exploited labor.

"As we're doing this work and putting the numbers into the database, we find a lot of Natives are enslaved, as well as African Americans who were purchased in the eastern half of the United States," she said.

Laws for indentured servants

Even though California prohibited slavery through the Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, passed in 1850, white families were allowed to file court petitions to grant authority over Native Americans as they saw fit, creating a binding contract for indentured servitude.

Tribes were routinely forced off their land, sent to reservations, and used as coerced laborers for construction of the Mission of Sonoma, ranchos, and other developments in the county.

News articles of the time report Native children were bought and sold in the northern part of the state. According to a January 10, 1861 article in the Nevada Democrat titled Indian Slave Trade in the Northern Part of the State, it states that "on pretty good authority – that stratagem and sometimes force, is made use of to capture the children, the consent of the children and their relatives being considered but of little importance."

Reviewing a November 19, 1860 court petition found in Indian Indenture Petitions records of the Sonoma County Court, the SSU history research team discovered an account of Native servitude and abduction.

The petition stated that a young Native girl named Francisca was living with her mother, Mary, a laborer for Thomas M. Ward, when she was kidnapped by her father Francisco and brought to Washington Guthrie's home in Santa Rosa.

"What we know is that Francisco abducted his daughter from her mother, who was living with Thomas Ward, and took her to Washington Guthrie's home," student researcher Carrillo said.

Because Francisca was now under the physical custody of Washington Guthrie, Carrillo said a court proceeding would be required for Thomas Ward to retrieve his indentured laborer.

The project’s beginnings

The research project was initiated through the Santa Rosa-Sonoma County NAACP after D'mitra Smith, NAACP's 2nd Vice President, presented at a COAR (Cotati Organized Against Racism) meeting.

"I was seeking data on slavery to better understand the history of the links to the Confederacy in Sonoma County, community reports of a generational culture of anti-Blackness and bias within law enforcement and county systems, and its potential links to reduced life outcomes for Black residents as outlined in the 2021 Portrait of Sonoma," said Smith.

"That report showed that Black residents live ten years less than any other racial or ethnic group and that Native American and Black residents respectively are most disproportionately represented within the unsheltered community," she said.

During the meeting, Smith and NAACP President Kirstyne Lange connected with Merith Weisman, former director of the Center for Community Engagement at Sonoma State. Weisman reached out to the History Department, and Kittelstrom answered.

"I'm a historian, and I work in facts. I'm committed to uncovering the truth of the past," Kittelstrom said.

Digging through county census records, state laws, and local newspapers from the late 1850s, Herrera said he "clearly saw a dark period in this county's history."

Smith said she is grateful for Kittelstrom's dedication to the historical facts and data the team has presented.

"I know she is committed to seeing this through. I'm excited that the NAACP can partner with Sonoma State University, and we can work together on this significant history that has been obscured for far too long," she said.

"The point of this work is to tell the stories of the people who have been overlooked," Kittelstrom said. "My experience regarding this project has been of most people cooperating, connecting with us and the data, and being excited about the research."

Hererra said that although this part of the county's history has not been significantly studied, every community must acknowledge the totality of its past, regardless of how negative it might be.

"This kind of research helps us come to terms with our past, learn from our mistakes, and take steps to mitigate the generational damage inflicted upon our family, friends, and neighbors," he said.

The Sonoma County Registrar, The Healdsburg Museum and Historical Society, and the Sonoma County History and Genealogy Library have all been instrumental in the work done by Kittelstrom and her student researchers.

Krista Sherer - Strategic Communications Writer