Second Chances for Inmates

Social Sciences Dean Elaine Leeder Advocates for the Incarcerated in New Book

If a professor teaches outside Sonoma State, it is often in summer school programs or day camps. When Elaine Leeder isn't being a dean or teaching sociology at SSU she teaches in San Quentin State Prison. She writes about her experiences there in her new book, My Life with Lifers, Lessons for a Teacher: Humanity Has No Bars.

Dean of the School of Social Sciences and Professor of Sociology at Sonoma State, her non-fiction work explains her experiences while teaching men serving life sentences in state prisons. Leeder's own perceptions of inmates changed since working with them and she now seeks to shatter stereotypes about prisoners being undeserving of a second chance at a normal life.

Leeder became involved with prison work while teaching a group of high school students at a summer program in New York. While taking the students to Elmira Correctional Facility for a tour, Leeder learned that the only education or self-help programs inmates had access to were GED programs and AA. She volunteered her time and expertise to the warden who happily accepted.

"There is little to no rehabilitation in prisons and if a prisoner is to transform, it is done through shear grit and determination, succeeding in spite of the system, not because of it," she said. Instead of assuming all prisoners are simply a lost cause, Leeder enables inmates to learn to do something positive with their lives when eventually released. Ninety five percent of all prisoners do eventually leave prison.

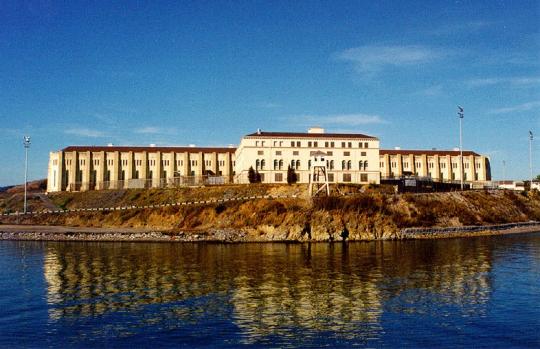

According to Leeder, many prisoners want very much to change. After moving to California, she started volunteering at San Quentin State Prison. Notorious for its reputation for housing exceedingly violent inmates, it was actually the prisoners themselves that were so inspired by Leeder that they asked her to start a permanent self-help program there. Named New Leaf on Life by the inmates, Leeder has been running the program since 2005.

"There are inmates I would never want to see on the streets, but they are the minority," said Leeder. There are many more who have rehabilitated themselves. Often they are in prison because of "the lack of opportunity which leads people to seek illegal means to meet their needs."

Leeder's interest in working with such people comes from her own personal background. Her father's family was killed in Lithuania during the Holocaust, her father having escaped to the US just before World War II. Her mother's family came from Poland and some suffered from mental illness and poverty. Instead of being disenfranchised by her family history, Leeder decided to try to right the social wrongs that lead to social problems.

"I have dedicated my life to remembering and speaking for marginalized members of society," she said.

Before her teaching career Leeder was a social worker in New York, working with victims of mental illness, alcohol and drug abuse. She taught sociology for over 20 years at Ithaca College in New York before moving to California and has always had an interest in "people who do not fit the norm."

Working in prisons has also opened her eyes to racial injustices within the justice system. In Leeder's book she states that there are now more African American men in prison than in college. In fact there are also more African American men in prison now than lived under slavery in 1865. At the same time the number of violent crimes is actually decreasing.

"I have learned much from my students, perhaps even more than they have learned from me," said Leeder. She now advocates decarceration and restorative justice programs, and wants to change society's perception of these criminals.

Much of what the public knows about inmates is based on reality shows such as "Lock Up," which are extremely biased; they show inmates at their worst. Leeder writes about the other side of prison life in her book, hoping that the public will become more forgiving and understanding when these men are released back into society.

"My experiences with men in prison have taught me that change is possible; after all prisoners are people too" she said.